End Times

Pandemics, Neiman Marcus, Nintendo, UFOs, and Remote Work

How Pandemics End

Lots of good historical context from Gina Kolata:

Bubonic plague has struck several times in the past 2,000 years, killing millions of people and altering the course of history. Each epidemic amplified the fear that came with the next outbreak.

The disease is caused by a strain of bacteria, Yersinia pestis, that lives on fleas that live on rats. But bubonic plague, which became known as the Black Death, also can be passed from infected person to infected person through respiratory droplets, so it cannot be eradicated simply by killing rats.

Historians describe three great waves of plague, said Mary Fissell, a historian at Johns Hopkins: the Plague of Justinian, in the sixth century; the medieval epidemic, in the 14th century; and a pandemic that struck in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The medieval pandemic began in 1331 in China. The illness, along with a civil war that was raging at the time, killed half the population of China. From there, the plague moved along trade routes to Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. In the years between 1347 and 1351, it killed at least a third of the European population. Half of the population of Siena, Italy, died.

Meanwhile, in another part of Italy:

In Florence, wrote Giovanni Boccaccio, “No more respect was accorded to dead people than would nowadays be accorded to dead goats.” Some hid in their homes. Others refused to accept the threat. Their way of coping, Boccaccio wrote, was to “drink heavily, enjoy life to the full, go round singing and merrymaking, and gratify all of one’s cravings when the opportunity emerged, and shrug the whole thing off as one enormous joke.”

That pandemic ended, but the plague recurred. One of the worst outbreaks began in China in 1855 and spread worldwide, killing more than 12 million in India alone.

Also:

It is not clear what made the bubonic plague die down. Some scholars have argued that cold weather killed the disease-carrying fleas, but that would not have interrupted the spread by the respiratory route, Dr. Snowden noted.

Or perhaps it was a change in the rats. By the 19th century, the plague was being carried not by black rats but by brown rats, which are stronger and more vicious and more likely to live apart from humans.

“You certainly wouldn’t want one for a pet,” Dr. Snowden said.

Another hypothesis is that the bacterium evolved to be less deadly. Or maybe actions by humans, such as the burning of villages, helped quell the epidemic.The plague never really went away. In the United States, infections are endemic among prairie dogs in the Southwest and can be transmitted to people. Dr. Snowden said that one of his friends became infected after a stay at a hotel in New Mexico. The previous occupant of his room had a dog, which had fleas that carried the microbe.

Such cases are rare, and can now be successfully treated with antibiotics, but any report of a case of the plague stirs up fear.

None of this is to say that what we’re living through now with COVID-19 is similar to the plague, but it’s fascinating context for the history of diseases. Read on for tidbits about smallpox and influenza, as well.

Right or wrong, I increasingly believe this will be the case:

One possibility, historians say, is that the coronavirus pandemic could end socially before it ends medically. People may grow so tired of the restrictions that they declare the pandemic over, even as the virus continues to smolder in the population and before a vaccine or effective treatment is found.

Again, that’s not necessarily a commentary or a stance — I just increasingly believe that’s how this is going to play out.

Neiman Marcus, the Retailer to the Rich, Files for Bankruptcy

Couple fun tidbits I never realized about Neiman Marcus, as relayed by Suzanne Kapner on the news of their bankruptcy:

Founded in 1907, Neiman Marcus came to epitomize the highest level of luxury retailing, dressing the oil tycoons of Texas and beyond in European finery.

The owners, Herbert Marcus Sr., his sister Carrie Marcus Neiman and her husband A.L. Neiman, almost invested their money elsewhere—in what was then an unknown bottled soft drink called Coca-Cola. “Neiman Marcus was established as a result of the bad judgment of its founders,” joked Mr. Marcus’s son, Stanley Marcus, in his memoir “Minding the Store.”

A near miss — maybe in both directions?

At the time, the journalist Edward R. Murrow, looking for ideas for his radio show, asked Stanley Marcus, who was then president of the company, what over-the-top Texans were buying for Christmas. Mr. Marcus pre-empted Mr. Murrow by offering for sale a Black Angus steer that could be ordered on hoof or in steaks—along with a silver-plated serving cart.

Neiman Marcus in the 1970s acquired Bergdorf Goodman, a Manhattan department store that caters to wealthy New Yorkers and tourists. It once carted over trunk loads of fur coats on Christmas Eve to John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s apartment, according to a 2013 documentary about the store called “Scatter My Ashes at Bergdorf’s.”

The option to order “on hoofs” was a nice touch.

Nintendo May Just Be Recession-Proof

Quite a year for Nintendo, as Jon Irwin (disclosure: a friend from college) points out:

Now, as the world’s population weathers a global pandemic, history stands to remind us that the toy company from Kyoto is not to be underestimated. After forecasting Switch sales of 18 million units and a net profit of 180 billion yen for the past fiscal year, Nintendo announced Thursday it had sold over 21 million consoles and made nearly 260 billion yen in profit. This March, they not only sold more units of their Switch console than during its launch in 2017, but sold the most consoles in a month for any platform in a decade. Another crisis, another unlikely victory.

And I mean, what timing for a certain game to come along:

In 11 days, ‘New Horizons’ sold over 11 million copies worldwide. The game has already outsold every other Animal Crossing title’s lifetime sales.

But it’s not just luck though, obviously:

But there’s more to Nintendo’s endurance than this lightning-in-a-bottle release. The company’s work has always pushed back against who can, or how they should, play games. They’ve been willing to experiment — and fail — because they’re fiscally responsible. More than anything Nintendo’s sustained success in times of crisis is due to the simple belief that joy matters.

Sometimes Nintendo misses with the attempts at creating joy — Wii U, anyone? — but when they hit, boy do they… As for their counterintuitive timing:

Financial adviser Serkan Toto said this is no accident. “With the NES, Nintendo intentionally entered a vacuum that opened up after the Atari shock of the [early] 1980s in the U.S.,” Toto wrote in an email to The Post. The games industry’s crash predated the larger financial crisis by four years; games’ value had been decimated by cheap cash-ins and poor quality control. Consumers were not going to spend their hard-earned money without good reason. Nintendo gave them a few.

“[The NES] came with distinctly high-quality games, was priced right and famously designed to look more like a VCR than a gaming console in order to overcome the stigma video games had back then,” Toto said. Film and TV enjoyed a higher cultural cache and was less intimidating to the older population — the same ones whose stock options had just plummeted.

Not all companies thrived in the wake of Black Monday. Atari was selling a new system, the 7800, to an underwhelmed population. Japanese competitors Sega had released their 8-bit Master System in the States one year prior and could only pull two third-party studios — Activision and Parker Brothers — away from Nintendo’s draconian licensing rules. That Christmas, the NES was the holiday’s top item according to trade magazine Toy & Hobby. A year later, Nintendo owned over 80 percent of the market, with Sega and Atari splitting the remainder. Today, both are out of the console business.

Take Those UFO Sightings More Seriously

Tyler Cowen on the notion of not dismissing the seemingly outlandish:

Among my friends and acquaintances, the best predictor of how seriously they take the matter is whether they read science fiction in their youth. As you might expect, the science-fiction readers are willing to entertain the more outlandish possibilities. Even if these are not “little green men,” the idea that the Chinese or Russians have a craft that can track and outmaneuver the U.S. military is newsworthy in and of itself. So would be a secret U.S. craft, especially one unknown to military pilots.

Also:

My own interest in the nature of UFOs stems partially from a somewhat unlikely source. I have spent a great deal of time in Nahuatl-speaking villages in Mexico doing fieldwork for a book. Residents of those villages are direct descendants of the Aztec empire, which met its doom when a technologically superior conqueror showed up: Hernan Cortés and the Spaniards. The notion that all of a sudden you are not in charge, and that the future will be permanently different from the past, is historically focal to them, as is the notion that there is more to the world than what is right before your eyes.

How Slack Became King of the Remote-Work World

Charles Fishman with just a fantastic profile of Slack:

If a company had 6,000 employees, it suddenly had 6,000 workplaces. If work sometimes seemed hard or frustrating to get done with everyone in the same place, now no one was in the same place. A technology like Slack quickly became the sinew that kept the functioning parts of the American economy connected. Across industries and geographies, the platform was proving indispensable—not just to information-age workers who were already fans but to the scientists scrambling to stop the virus and the people keeping New York City’s subways rolling through the pandemic.

He goes on to talk to everyone from rural farmers to city transit workers on the importance of the tool for the day-to-day. Also, life science companies working on the virus itself:

The whole effort took place over Slack. “It was essential,” Bouhaddou says of the platform. This sprawling team of experts was able to stay in touch constantly so that people didn’t make mistakes or drift too far from each other. At all hours of the day and night, the scientists traded questions, insights, theories, techniques, and results. They shared working diagrams to be included in the paper, so everyone could check and adjust them. Bouhaddou says that he sent or read Slack messages every couple of minutes. “It was just like being able to turn to a colleague right there in the lab and say, ‘Am I thinking about this right?’ and get an answer right back,” he says. “Except the colleague was across the city, or in Paris.”

Finally:

Whether or not the spike impresses Wall Street, in the crisis, Slack is helping make sure that milk gets to stores, that New York’s doctors can get to hospitals, that the world’s scientists can unmask the coronavirus. Says Butterfield, “There’s a feeling inside the company that we were made for this.”

Asides

Took me a while to get around to Steven Sinofsky’s thoughts/tweetstorm about the iPad unveil (released while he was within Microsoft), but well worth it.

Speaking of Windows, no surprise that Microsoft’s dual-screen “Windows 10X” products are being delayed indefinitely. COVID situation aside, these have never passed the gimmick smell test.

John Hanke (CEO of Niantic, where my wife is COO) with a great post about the importance of walking. Outside. Especially now.

The news that Taika Waititi will direct and co-write a new Star Wars is fantastic. Note that the language makes it pretty clear that this will be a feature film, and not a Disney+ series or the like. Also, the first one to be co-written by a woman since The Empire Strikes Back.

Speaking of Star Wars films, and things that I’m late to — boy, does Colin Treverrow’s supposed treatment of the last Star Wars film sound good. Much better than what we got, unfortunately.

500ish

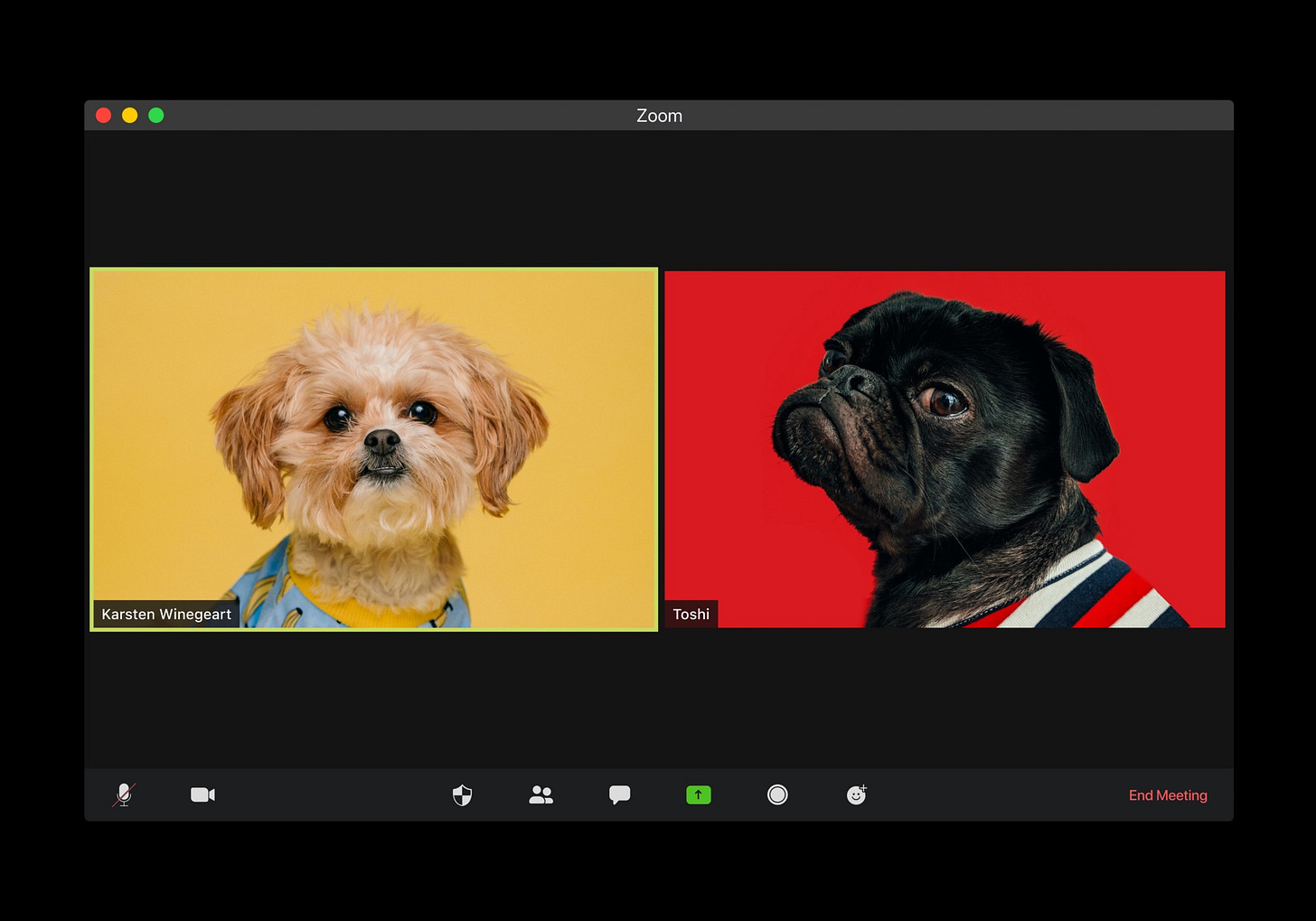

The Brutal Efficiency of Zoom

A funny thing happened on the way to optimizing work…

Cut, Copy, Paste, & Highlight

An idea for iOS and Android…